During the past two years I’ve read a lot about bereavement and the difficulties associated with navigating a new and unfamiliar world. I suppose the hope is to be somehow reconnected through the shared experiences of others. To learn ways of coping and to benefit from any nuggets of wisdom. But what I’ve concluded is that grieving for a loved one is just about the most personal journey a human being is likely to undertake. The five stages of grief, as noted by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross - denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance - will inevitably be referenced during counselling or maybe parroted by your GP, and I admit that it’s been helpful to have these headings to file my feelings under although, emotions being emotions, they don’t arrive in any given order.

I imagine anyone observing the behaviour of someone recently bereaved might worry that the individual concerned has shifted onto a path littered with episodes of irrationality. The once predictable head now betraying it’s jumbled contents through half answered questions, impulsiveness, and unreliablity.

I recall a time in my teens when a neighbour died suddenly while attending a football match. Within days his wife had her hair dramatically restyled, put her husband’s record collection out with the refuse, and arranged for an immaculately maintained hedge to be cut down and grubbed up. Years later, when we lived in Cornwall, a close neighbour died after a short illness. His wife, who rarely went out other than to visit family and friends, suddenly developed a dizzying social calendar and became deeply involved with a bereavement charity. She then sold up and moved to Devon. These are the kinds of changes we are privy to as outsiders looking in. The unexpected actions of people we thought we knew. The internal, deeply personal day to day patterns that border on the chaotic, I think, go largely unobserved. The paralysis, the weeping, the night-time panic attacks that leave you feeling hungover in the morning.

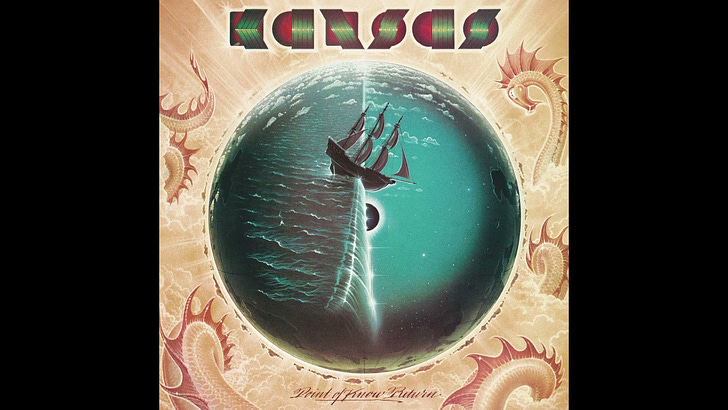

For my part I have been rather like a ship with a wonky rudder as described by Michael Palin when an interviewer touched on the recent loss of the former Python’s wife. Sailing along steadily, then, without warning, finding myself trying wildly to reconnect, like a demented electrician replacing blown fuses with one hand while attempting to twist and join feeble strands of bare flex with the other.

But therapy is helping. It really is. The one hour sessions fly by. I always leave with a sense of achievement. Goodness knows what I’ve talked about. My life I suppose. I initially sought help to make sense of losing Mags but grief appears to be a house with many rooms. I’ve entered a few of them during these past few weeks that have been locked and boarded up for a long long time. Only in the safe environment of the therapist’s room have I felt confident enough to hold my breath against the stale air of the past while reaching forward to throw open the shutters. Amazing what the light reveals.

I think it was an Alan Watts quote that summed up the brevity of life as “a brief spark between two dark unknowns.” However we describe it, the fine line of unknowable distance is one that we all walk. Gaining an understanding of what makes us tick is as good as a tightrope walker’s balancing pole, increasing our moments of inertia and so enabling us to proceed forward at our own pace with a reduced risk of slipping.

"..a house with many rooms..." What an excellent image. I'm glad to hear that the therapy is proving helpful.